https://mildurarsl.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Screenshot-2024-07-22-131346.jpg

337

1442

RSL

/wp-content/themes/custom/assets/img/mildura-rsl-logo-padded-large.png

RSL2024-07-22 02:56:292024-07-22 05:29:22MILDURA RSL ANNUAL REPORT

https://mildurarsl.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Screenshot-2024-07-22-131346.jpg

337

1442

RSL

/wp-content/themes/custom/assets/img/mildura-rsl-logo-padded-large.png

RSL2024-07-22 02:56:292024-07-22 05:29:22MILDURA RSL ANNUAL REPORTPaintbrush is Prowsie’s weapon of peace

AUG 12 2023

LAURA TURNER

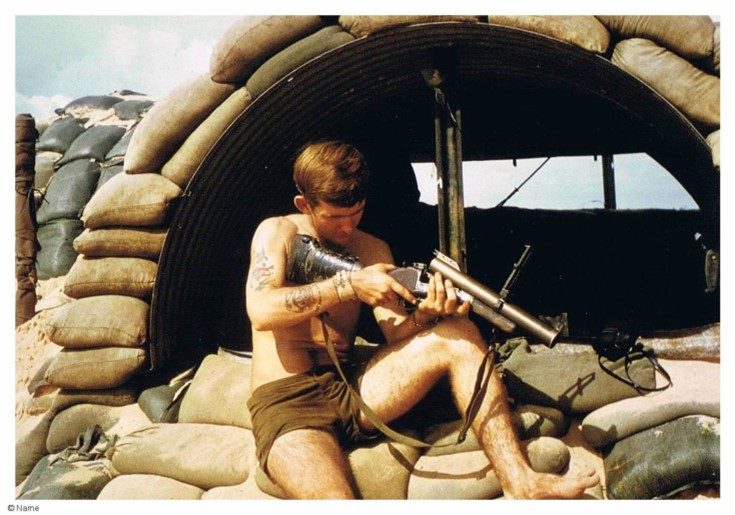

John Prowse with a grenade launcher at 7RAR’s fire support base Bridget, near the town of Phuoc Hai in Vietnam.

Vietnam veteran John Prowse with a selection of his works. Picture: Ben Gross

Little John Prowse grew up with a paintbrush in his hand and vibrant pictures in his head but, when he was sent off to war, he found himself on both ends of a bayonet. The artist known as Prowsie tells LAURA TURNER how his award-winning talent has helped him win his own private battle.

IN a tiny bedroom on Olive Avenue sits a little boy.

He’s bent over a pad of clean white paper, his imagination pouring down onto the page.

As the wild ideas of a post war Australian boy come to life, young John Prowse is interrupted by a knock at the door. It’s his mates, keen for a kick down the oval.

“Come on Prowsie, come and play footy,” John remembers them calling.

“And I’d say: ‘No, I’ve got a comic to finish’.”

Mates are extremely important to the man now known as Prowsie. This is a fact that was galvanised when he boarded the HMAS Sydney in 1969.

His generation was called to serve in a war that would in the end turn them into social pariahs with life-long scars.

But even with a bayonet in his hand, John was still an artist and he remembers his comrades laughing at him for transforming the inside of his bunker. He did away with the old tin walls with a lick of glossy blue paint and hung his cards and postcards along a string for decoration.

In their final days in Vietnam, John remembers he and his mates belting out the song “We gotta get outta this place”, and it’s a song that still evokes awful memories of his time served.

But there were also some hilarious times, none more so than when he and his mates Johnny and Sonny were standing on the landing barges ahead of the arrival march in Townsville.

“I said to Sonny: ‘Lift me up on your shoulders and I’ll see if there’s any Australian birds on the beach,’” he remembers.

“We hadn’t seen Australian women for a long time. Anyway he put me on his shoulders and said what’s it like? I said, “Oh mate, this is going to be great!”

What John didn’t see was the bloke polishing his bayonet in front of them.

“I fell off Sonny’s shoulders and the guy was putting his bayonet back and it slit me across the stomach,” he laughs as he says, “I almost got killed perving on an Australian woman after all that shit in Vietnam.”

So off he went on the march with blood seeping through the tear in his shirt.

But the laughter faded as each of their boots struck dry ground down the main street. When nasty comments and even spit started flying from pockets of the crowd, John and his mates were wounded in a way they never expected. Far from the battlefields of Vietnam, the politics of a divided Australia meant these men were traversing a landscape thatched with the voices of anti-war activists willing to draw their own weapons on the men who had no choice but to participate in combat.

John remembers how much the abuse hurt.

“All the blokes were still trying to get over their mates dying and what we saw over there and it affected the whole lot of us.”

A post-march afternoon at the pub helped bury the trauma, but even with too many beers under their belts, they couldn’t help but notice how at the end of the day they were all crammed onto old cattle trains and sent on their way. “The way we were thrown on, I thought: ‘This is a great homecoming, isn’t it?’” says John.

The hilarity of mateship again superseded any upset.

When they noticed one bloke was missing. “I said to my mate: ‘Where’s Sonny? For god’s sake, we’ve lost Sonny!’”

John’s mate noticed something moving down the tracks in the distance.

“We looked out the back window and there he is running down the track, trying to catch up with the train with a big slab of beer in his arms.”

Arriving home in Mildura had a much nicer feel to it, but it was on the front porch of the family home in Olive Street that his mother started screaming at the sight of her son. He didn’t realise he’d arrived home with blood splattered all over his shirt. What his mother didn’t realise is that it wasn’t John’s blood. He’d broken up a fight on the way home.

John spent the next few years moving around Adelaide and Melbourne as a ticket writer and merchandiser for displays in department stores like Georges and John Martins. Jobs and marriages came and went, and his constant companion was his paintbrush.

Portraits of Hollywood stars were some of John’s earliest works which then evolved into the exquisite depictions of Australian animals and vibrant watercolours that he’s now so well-known and acclaimed for.

That artistic flair weaved its way into his presidency of the Mildura Vietnam Veterans Association.

In an effort to raise money for war widows, John introduced the “no talent” show at the RSL which called for volunteers to get up on stage and entertain the crowd.

“Kim the manager said to me: ‘Prowsie, this won’t work,’” John remembers.

But just as they were about to bring the first act onstage, an old man with a harmonica turned up asking for a shot in the show.

Despite having the set list already organised, John didn’t think he had anything to lose, so let the man go first. He watched as the man called over a “lah dee dah-looking” woman from the crowd.

“He calls her over and says: ‘Can you get me a glass of water?’ So she gets him a glass of water and brings it over and he says ‘now just stand there and hold it for me’.

John tells me the woman obliges and, “just before he starts playing he took his teeth out and dropped them in the glass. The place erupted in laughter. The look on the woman’s face with the false teeth floating down the glass, she was nearly passing out,” he says rocking back, laughing.

After John’s second marriage ended, he admits he started drinking too heavily and found himself moving around a lot.

“I started painting full-time to get my mind off things,” he says.

It certainly seems to have worked.

In the same little house on Olive Avenue, more than 50 years after John Prowse went to war, he now lines the walls with his award-winning art work.

As he passionately describes to me the process of creating a watercolour, I think to myself this is a man who knows it’s the paintbrush, not the bayonet. that defines who he is.

Article written by: Laura Turner

Article provided by The Sunraysia Daily

https://www.sunraysiadaily.com.au